University of Illinois, Chicago

Undoubtedly, the feminist anti-violence movement has improved awareness about and resources for women victims of domestic violence since the 1970s. The availability of domestic violence advocates in hospitals and courts is just one example of such improvements. While medical and mental health professionals in the 1970s and 1980s were likely to characterize domestic violence victims as having “Battered Women’s Syndrome” or a related psychological disorder, these types of overtly pathologizing labels have waned in popularity. And yet, the ways in which domestic violence victims are represented and surveilled in the biomedical field today are not without problems. Though domestic violence victims’ health is much more likely to be described and diagnosed today through the language of “chronic” suffering and “trauma,” the question remains: is this really a more just and empowered characterization of domestic violence victims, or is it simply a more subtle form of victim-blaming?

In a recent Social Science & Medicine article, I explore this victim-blaming question by analyzing the ways in which victims’ bodies are represented in biomedical literature from the 1970s onward. I found that medical journal articles in the 1970s and 1980s focused on women’s domestic violence injuries, whereas medical representations of domestic violence victims after 1990 focus much more chronicity and long-term “health behaviors.” While the latter may seem more intensive and forward-thinking, this “chronic” construction of domestic violence may also expose women’s bodies to more and more medical redefinitions and interventions, ramping up domestic violence victims’ burdens to be more “responsible” health citizens.

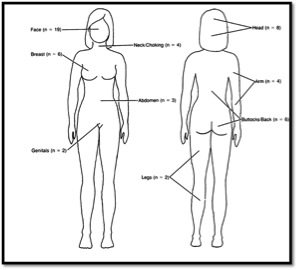

Early articles discussed direct assaults to the body: bruises, gashes, broken bones. In this characterization of domestic violence victims, injuries are immediate and obviously medical. Consider this image taken from an American Journal of Public Health article in 1987:

The diagram tallies the number of injuries that women in the study had in each, discrete region of their bodies. Injuries are easily locatable on the physical body. While the effects of domestic violence on the woman’s body remain relatively surface-level here, women’s overall health problems were conceived of mostly in psychological terms. Doctors and researchers used labels like Battered Women’s Syndrome to explain the “deep” and long-term effects of domestic violence, marking women’s psyches as damaged with terms like “learned helplessness.” Victims’ bodies, on the other hand, sustained acute injuries that were amenable to straightforward medical attention.

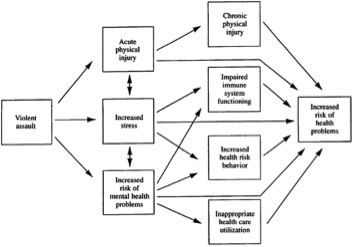

Once Battered Women’s Syndrome and other such diagnoses fell out of favor in professional circles (i.e. medicine, social work), the way that biomedical literature represented victims’ bodies also changed. Tired images of battered women with Stockholm Syndrome-like symptoms lost most of their influence in professional circles during the 1980s and 1990s. What came to replace these images was a more “active” domestic violence victim, a victim whose injuries are not easily identifiable on the physical body, a victim whose problems are more subtle and continue to plague her on and on into the future. This newer representation of domestic violence victims is deployed primarily through the language of “chronic” conditions. This diagram from a 1997 Behavioral Medicine article provides a useful comparison with the previous image:

In this diagram, violent assault is followed by acute injuries and immediate stress, but the bulk of the arrows point to more abstract “health problems” such as chronic illness, long-term biological dysfunctions, and poor health behaviors. The difference between this diagram and the previous diagram is important – what were once discrete, identifiable injuries are now generalized and “long-term” health problems with complex origins. The experience of domestic violence becomes installed in a victim’s body and then sends shockwaves of effects throughout her future. The list of possible conditions that result from domestic violence is now seemingly endless: “heart attack,” “stroke,” “infectious diseases,” “seizures,” just to name a few. Here, abuse is everywhere inside the body.

When the psychological focus of Battered Women’s Syndrome recedes in popularity, the medical literature begins to represent abused women’s bodies as chronically sick. This shift is significant for victim-blaming in a number of ways. Because health problems are regarded as “intrusive” for a long period of time following abuse, the woman’s entire future is at stake. In one article, for example, the authors note that, “In addition to the impact on individual health and wellbeing, violence against women takes an enormous social toll in terms of medical costs, decreased work productivity and an increased burden on the justice, social, and health systems” (Montero et al., 2011, p. 295). Here, the identification of domestic violence as a chronic diagnosis jeopardizes victims’ futures in all sorts of ways, making them a “burden” on the system. It is not just that victims cause the system to sustain more costs, but blame is worked deeper inside their bodies. It is as if domestic violence installs a vulnerability inside victims, forcing their bodies to constantly reproduce negative outcomes. For example, in a 1997 article, the authors argue that domestic violence exposure increases the risk of “poor health behaviors” such bad diet and drug use. Another article suggests that abused women's “anger/hostility” following abuse may diminish good health outcomes. Here, abuse is the source of victims' “bad” health behavior. Vulnerability to abuse is situated so deeply here that victims continue to feel its effects and act on its behalf without knowing it. Abuse becomes incorporated.

So, what does this representation of abuse as embodied tell us about progress for domestic violence victims in the biomedical field? First, this story of the shift from “injury” to “chronic” representations of abused women suggests that victim-blaming tropes do not disappear when Battered Women’s Syndrome and other such pathologizing diagnoses fall out of favor. Rather, ideas about victims’ bodies as disordered and pathological are reinvented in a different language. Rather than marking women as crazy and weak, new medical representations of abused women mark them as badly embodied, their whole somatic futures subject to ongoing disorder. The notion of “progress” is not simple, then. While victims are less likely to be overtly labeled with pathologizing disorders than they were in the 1970s and 1980s, they may actually be subject to more biomedical surveillance today because of the “chronic” language now in use. Increased awareness about domestic violence means that we must also contend with the increased risks of medical screening and diagnosis, or the transformation of the complex social phenomenon of domestic violence into a diagnosable and biomedically treatable chronic “condition.” Thus, the construction of this chronically ill domestic violence victim makes more aspects of victims’ lives subject to redefinition via medical diagnosis. Blaming women for the abuse they suffer is by no means a new phenomenon, but under new chronic labels, it has a powerful biomedical veneer, giving it fuel to travel to new regions of the body, to deep features of the future self.

References

Helton, A.S., McFarlane, J., Anderson, E., 1987. Battered and pregnant: a prevalence study. Am. J. Public Health 77 (10), 1337-1339.

Montero, I., Escriba, V., Ruiz-Perez, I., Vives-Cases, C., Martín-Baena, D., Talavera, M., et al., 2011. Interpersonal violence and women's psychological well-being. J. Womens Health 20 (2), 295-301.

Resnick, H.S., Acierno, R., Kilpatrick, D.G., 1997. Health impact of interpersonal violence 2: medical and mental health outcomes. Behav. Med. 23 (2), 65e78.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed