PhD Candidate in Sociology

Yale University

In 2012, while perusing an online breast cancer community board, a discussion thread provocatively titled “I look for other flat chested women. A rant” caught my attention. The author of the post, Melanie, urged non-reconstructed breast cancer survivors (I am one) to join together and make themselves visible. She wrote (emphasis mine):

I want to see you. I want to form a union […]. I wish it were […] acceptable to be flat. To not wear prosthesis, not feel the need to, to opt out of reconstruction—if that is your choice. I do hope that women who see me, flat as can be, see there are options, that reconstruction isn’t par for the course. I want to make flat beautiful, sexy, stylish. Normal. And it is normal for me, is becoming normal, but I am talking about society, norms and expectations. (Excerpted from melanietesta.com)

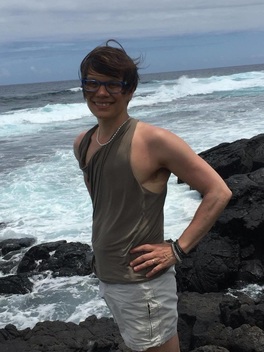

Mixed media artist, author and

Mixed media artist, author and teacher Melanie Testa.

Photo courtesy of David Romine.

Melanie’s critique of social expectations of women’s chests reminds me that we are aesthetically “framed by gender…before we know it” (Ridgeway 2009:148). Whereas in infancy the symbolic production of binary gender, which, being presumptively “appropriate to the anatomy of the infant” (Pieretti and Donahoe 2013:945), requires a body in possession of aesthetically discrete genitalia, in adolescence and adulthood aesthetic differences in breast tissue play a key role in the construction of legal and social gender. In states requiring surgical reassignment to change one’s gender marker from female to male on vital records, mastectomy is often the only surgery required (Markowitz 2008). And on the opposite end of the spectrum, female-identified breast cancer survivors considering their post-mastectomy options may find themselves confronted by medical discourse informing them that breast reconstruction is vital to restoring not only their femininity but their very identity (Cash N.d.; Crosby 2010).

What intrigues me about juridico-medical practices such as these is their conflation of that which social constructivist theory has decoupled—anatomy and gender (see Fausto-Sterling 2000; Lorber 1994). Along with female-to-male gender reassignment policies that mandate mastectomy as part of creating a masculine chest, the rhetoric of “reconstruction” and “restoration” in breast cancer discourses sequesters femininity in the breast; for the language of restoration, in contrast to, say, rejuvenation, presupposes something evacuated. One outcome of these practices is the sanctification of a dichotomously gendered breast aesthetic: i.e., mounded and curvilinear as feminine; flat and angular as masculine. Another is the employment of the denotative schema of the absent versus present breast to hyperbolize the putatively natural dimorphism of the sexes.

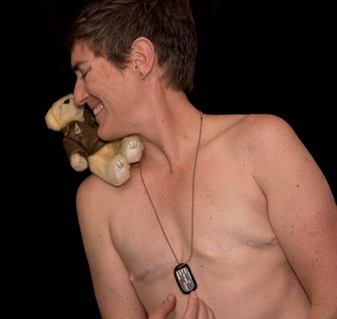

Former U.S. Marine officer Kyleanne Hunter is the

Former U.S. Marine officer Kyleanne Hunter is theco-founder and co-director of the Think Broader Foundation.

Photo courtesy of Carol Sternkopf Photography

I hear murmurs and whispers in locker rooms of being “freakish,” “mannish,” “grotesque,” and “ugly.” In survivor and support groups I have been questioned as “butch.” In conversations I have been told that I am “clearly a trans man” and that my opinion on my womanhood “doesn’t matter,” since I present more androgynously than I did when I had boobs. […] Changing from my work clothes, I was approached by a woman. “You don’t belong in here!” she screamed. She pointed to my scars and said, “I don’t care what you think you are, but you are clearly a man trying to pervert this space reserved for women!”

What I find striking in the dialectical interplay between the present/absent breast and sensible/insensible femininity is the interpretive role that iconic consciousness asserts in how individuals embody meaning and the way they make gendered sense of their own as well as other people’s bodies. In Iconic Power, Bartmański and Alexander describe iconicity as the interaction between material surface and symbolic depth, specifying that “actors have iconic consciousness when they experience material objects, understanding them cognitively but also feeling their sensual aesthetic force” (2012:1). Hence, the aesthetic ‘power’ of the breast, and the body more generally, is always a relation construed between material surface, social meaning, and the sensuous depths of individual experience. One implication of this construal in cases of female mastectomy is that the disjunction of material surface (signifying breast) from its discursive depths (signified gender) can dissipate the iconic power – or the expedient comprehensibility – of that particular material aesthetic.

In their communicative capacity, icons contrast, condense and transmit meaning similar to how the refractive lenses of a lighthouse focus and magnify light. The more concentrated the beam, the greater the intensity, the greater the distance from which it can be seen. Or by way of analogy, the more mimetically clear the icon, the more it comports with shared cultural representations, the more readily its social meaning can be apprehended. Thus, as icons of female gender, breasts anchor social meanings of femininity – e.g., moral prescriptions about how women should look and act – in the mounded, curvilinear material form of the designated female chest. Just as the meaning of the lighthouse beacon, as opposed to its substance, directs ships away from rocky shores, the iconicity of the breast influences social action and interaction, determining, for example, which bodies may go topless in public, which bodies are eligible to change their gender marker, and as Hunter’s experience reveals, which bodies belong in the ladies locker room.

Though I find the visual semiotics of breastedness in social life a compelling analytical frame through which to understand yet another interactional mechanism for making collective meaning by “doing gender” (West and Zimmerman 1987), what is of greater interest to me is examining how aesthetic feeling and/or sensibility entailed in iconic consciousness can inform individual meaning-making. Interviews I conducted between 2014 and 2015 with ten transmen and seventeen breast cancer survivors who have undergone mastectomy reveal an attendance to personal aesthetic feeling, not just concern about risk of recurrence or social stigma, when considering their surgical options and evaluating their post-mastectomy outcomes. All nine of the non-reconstructed breast cancer survivors I spoke with emphasized the feelings of freedom and flexibility that came with being flat-chested. Tummy sleeping was more comfortable (‘no breasts to shift’), running was more enjoyable (without ‘them things flopping around’), going topless was now an option, and with prostheses one could experiment with a variety of cup sizes.

The scope of this post precludes me from enumerating examples, but findings from my interviews with mastectomy patients suggest that aesthetic feeling educes a sense of body-gender integrity via perceptions of pleasure, comfort, freedom, flexibility, harmony, beauty, etc., and their respective contrasts. In Just One of the Guys, Kristen Schilt (2010) posits that feelings of pleasure derived from experiences of sex/gender coherence may account for the intractability of natural difference schemas and the form of the male/female binary. (The content of the gender binary, she argues, “has changed widely” [p. 175].) Based on my own research I would add that just as the pleasure of coherence may direct individuals toward iconic embodiments that reify the gender binary, it also can lead them toward iconoclastic embodiments such as breasted masculinity or flat-chested femininity. Accordingly I believe that iconic consciousness, especially because it operates in the realm of individual experience as well as social life, constitutes a fecund reservoir of potential cultural change. For when a flat, angular chest ceases to be a reliable signifier of masculinity, then that material aesthetic loses its capacity to make things happen in the world in a patterned and consistent manner.

Vonn Jensen is the founder of Flattopper Pride.

Vonn Jensen is the founder of Flattopper Pride. Photo courtesy of Alessandra Pace and Fausto Serafini

References:

Bartmański, Dominik and Alexander, Jeffrey C. 2012. “Materiality and Meaning in Social Life: Toward an Iconic Turn in Cultural Sociology.” Pp. 1-23 in Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life, edited by J.C. Alexander, D. Bartmański and B. Giesen. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Beauvoir, Simone de. [1949] 2011. The Second Sex. Translated by C. Borde and S. Malovany-Chevallier. New York: Vintage Books.

Cash, Camille, M.D. N.d. “Breast Reconstruction.” (http:www.camilecashmd.com/breastenhancement/breast-reconstruction.cfm).

Crosby, Melissa A. 2010. Reshaping You: Breast Reconstruction for Breast Cancer Patients. Patient Education Office: Booklet. Houston: The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge.

Fausto-Sterling, Anne. 2000. Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of

Sexuality. New York: Basic Books.

Lorber, Judith. 1994. Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lorde, Audre. 2006. The Cancer Journals. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

Markowitz, Stephanie. 2008. “Change of Sex Designation on Transsexuals’ Birth Certificates: Public Policy and Equal Protection.” Cardozo Journal of Law & Gender 14(3):705-730.

Origin Magazine. 2016. “Origin Fem Series: Kyleane Hunter, Former U.S. Marine Officer, Co-Founder of Think Broader Foundation.” Origin Magazine, April 27. (http://www.originmagazine.com/2016/04/27/origin-fem-series-kyleane-hunter-former-u-s-marine-officer-co-founder-of-think-broader-foundation/).

Pieretti, Rafael V. and Patricia K. Donahoe. 2013. "Surgical Treatment of Disorders of Sexual Development." Pp. 945-966 in Operative Pediatric Surgery, edited by L. Spitz and A. Coran. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 2009. “Framed Before We Know It: How Gender Shapes Social Relations.” Gender & Society 23(2):145-160.

Schilt, Kristen. 2010. Just One of the Guys: Transgender Men and the Persistence of Gender

Inequality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

West, Candace and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society 1(2):125- 151.

Williams, Lena. 1991. “Women Who Lose Breasts Define Their Own Femininity.” The New

York Times, December 25. (http://www.nytimes.com/1991/12/25/health/women-wholose-breasts-define-their-own-femininity.html).

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1991. The Fine Line: Making Distinctions in Everyday Life. IL: University of Chicago Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed