| by Elise Paradis Assistant Professor University of Toronto Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy & Department of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine Scientist, The Wilson Centre I have recently crossed the street into a new job, leaving my office in the bustling core of the Toronto General Hospital for a new office on the 7th floor of the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy. As a sociologist, working in a hospital never felt “natural,” but landing in a Faculty of Pharmacy is no less strange: Who would ever have thought that a leftie feminist like me would end up here? It surprised me and my loved ones equally; but this is another story. As a student of the body, who has conducted two ethnographies in apparently different but uncannily similar environments – the boxing gym (Paradis, 2012, 2014a) and the intensive care unit (Leslie et al., In Press; Paradis, Leslie, & Gropper, Under Review; Paradis et al., 2014) –, I have learned to pay close attention to what I used to call “my ethnographic |

In our study of care team interactions in the ICU (Paradis, 2014), however, my body and how it was perceived seemed completely beside the point... until I realized that depending on what I was wearing, I was perceived differently. I was seen as a student when wearing jeans and sneakers; as an attending physician (staff physician in Canada; consultant in the UK and Australia) on Tuesdays when I tend to wear a tie; and as a physical therapist the rest of the time for my perceived athleticism and my civilian clothes (see Jenkins, 2014 on clothing and status in healthcare).

In a move parallel to the move from self to identity in sociological theory, these experiences have made me reconsider my relationship to my “ethnographic body.” I now see ethnography bodies. This reconsideration is reminiscent of Annemarie Mol’s “body multiple” (Mol, 2002), yet the shift here is not ontological: it is not when I take on a different perspective on what is real that my body changes. Rather, it is through its embeddedness into a context – or field, since I am very much a Bourdieusian – that my body crystallizes into one version of itself: the athletic body, the female body, the student body, the physiotherapist body. In fact, I have come to believe that I do not have a bodily self; rather, my body has an identity that shifts according to my location in social space, the actors I interact with, and how they read and value my body.1

In the hospital, I didn’t really “fit” in any of the main categories of hospital human resources. I was neither someone who cared for the ill nor an ill person myself. I was not part of the administration, nor part of the maintenance crew. Walking through the halls of the hospital, my discomfort was generally a low hum, muted until it was activated by a passerby who wanted guidance to find the red blood cell disorders clinic, or by someone in line at the coffee shop who shared the story of a surgeon in this hospital who, ten years ago, saved his life through a successful heart transplant. Those experiences made me feel slightly parasitic, aware as I am that my existence in this hospital context has been enabled by a Canadian (if not global!) health research enterprise that values interdisciplinarity and has placed several social scientists and humanities scholars like me into clinical faculties (especially medicine) around the country. Colleagues and I have written about the experiences of these scholars (Albert & Paradis, 2014; Albert, Paradis, & Kuper, 2015, Forthcoming), yet we haven’t covered this sense of being physically or bodily out of place, the sense of being neither here (in the hospital) nor there (in a social science department), of living in a liminal space.

Crossing the street into a more traditional academic setting three months ago made me reconsider my bodily identity once again. Strangers generally see me as someone who is in her mid 20s to mid 30s, and I thus stand in an imprecise relationship to the undergraduate students whom I cross in the hallways (and whom I will soon be teaching), and in an even more imprecise relationship to the graduate students, staff and other faculty members who have yet to “learn” that I am one of the new tenure track hires.

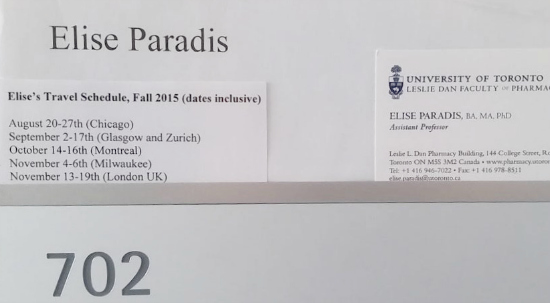

On Wednesdays, four different groups of 60 undergraduate pharmacy students in white coats wait for their pharmacy practice laboratories in the hall right in front of my office door, sitting and standing in small clusters, chatting. Every time I have to navigate the crowd, make my way through the white-clad bodies of students who haven’t yet met me, I wonder how they see me, how they “bin” me into one of the categories of people who have offices on that floor.2 About a month ago, I put my business card up behind the Plexiglas that holds my name (see Photo). “I might look young, and you might not know me, but I’m legit; here are my creds,” I felt defensively as I slid the card between paper and Plexiglas. I will not lie: writing this blog has made me ashamed of this silly, juvenile insecurity, and I took down the card after snapping the attached picture. My invisibility is something that in any other context I value: in the elevator, it allows me to listen to what students say while staying under the radar; for my upcoming ethnographic study of the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, I wish I could at once earn students’ trust and spy on them freely, but as soon as I start teaching them, deception will become impossible.3 Yet in my new work context, where I am the new kid on the block ensconced in a body that often looks decidedly non-professorial, I felt the need to legitimate my existence.

In conclusion, it is a truism that at the core of contemporary ethnography is an understanding that the ethnographer is the instrument of data collection, and therefore the medium through which information must pass before being acknowledged as important, written up as fieldnotes and then being made part of ethnographic accounts. We show we care about the subjectivity of the ethnographer through emphasis on reflexivity on previous experiences and relationships to the people and topics we cover. Too often, however, the ethnographic bodies have no place in these accounts. What if we considered our bodily identities in our ethnographic research, documenting how they impact our perspectives? What if we troubled the idea of a single, lived experience of the body, and instead worked to document the many bodily identities of our research participants? What would an ethnography of bodily identities look like?

Notes

1 Loïc Wacquant and I have been engaging in a conversation about the meaning of habitus and field in print in the context of boxing over the past few years; see Wacquant (2004); Paradis (2012); Paradis (2014b); Wacquant (2014); and Atkinson (2015).

2 Most of my colleagues on the 7th floor are pharmacists whom the Faculty calls “clinician scientists” because they teach undergraduates and conduct research on pharmacy practice. They have shared similar struggles with navigating the sea of white-coat-clad bodies on Wednesdays. On the 6th floor, below, faculty members have their names listed as “Dr. So Andso,” while I am “Elise Paradis.”

3 A colleague suggested that students do not always self-censor, even in front of faculty whom they know.

References

Albert, M., & Paradis, E. (2014). Social scientists and humanists in the health research field: A clash of epistemic habitus. In D. L. Kleinman & K. Moore (Eds.), Handbook of science, technology, and society (pp. 369-387). New York, NY: Routledge.

Albert, M., Paradis, E., & Kuper, A. (2015). Interdisciplinary promises versus practices in medicine: The decoupled experiences of social sciences and humanities scholars. Social science & medicine, 126(1), 17-25.

Albert, M., Paradis, E., & Kuper, A. (Forthcoming). Interdisciplinary fantasy: Social scientists and humanities scholars working in faculties of medicine. In S. Frickel, M. Albert, & B. Prainsack (Eds.), Critical studies of interdisciplinary research. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Atkinson, W. (2015). Putting Habitus Back in its Place? Reflections on the Homines in Extremis Debate. Body & Society, 1357034X15590486.

Jenkins, T. M. (2014). Clothing norms as markers of status in a hospital setting: A Bourdieusian analysis. Health:, 18(5), 526-541. Retrieved from http://hea.sagepub.com/content/18/5/526.full.pdf

Leslie, M., Paradis, E., Gropper, M. A., Milic, M. M., Kitto, S., & Pronovost, P. J. (In Press). A Typology of ICU patients and families from the provider perspective: Towards patient centrism. Health Communications.

Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice: Duke University Press.

Paradis, E. (2012). Boxers, briefs or bras? Bodies, gender and change in the boxing gym. Body & Society, 18(2), 82-109.

Paradis, E. (2014a). Skirting the issue: Women boxers, liminality and change. In lisahunter, W. Smith, & e. emerald (Eds.), Pierre Bourdieu and physical culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Paradis, E. (2014b). Sociology is a martial art: A commentary on Wacquant's Homines in Extremis. Body & Society, 20(2), 100-105.

Paradis, E., Leslie, M., & Gropper, M. (Under Review). Interprofessional Rhetoric and Operational Realities: An Ethnographic Study of Rounds in Four Intensive Care Units.

Paradis, E., Reeves, S., Leslie, M., Aboumatar, H., Chesluk, B., Clark, P., . . . Kitto, S. (2014). Exploring the nature of interprofessional collaboration and family member involvement in an intensive care context. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(1), 74-75. doi:10.3109/13561820.2013.781141

Wacquant, L. (2004). Body & Soul. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wacquant, L. (2014). Putting Habitus in its Place: rejoinder to the symposium. Body & Society, 20(2), 118-139.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed