Sociology at Fredonia, SUNY

Election time always provides a snapshot of how race shapes just about everything in American politics. The Democratic Party spent this past election season rallying black voters to vote Democrat in a desperate attempt to hold onto the Senate. It worked, but they still lost control of Senate. The president nominated Loretta Lynch to replace Eric Holder as US attorney general. If confirmed, Lynch will be the first black woman to hold the post. Holder was first black US attorney general. The GOP also wooed black voters this past election season. A GOP Super PAC paid black leaders to support Thad Cochran in the Republican Primary run-off in Mississippi. Cochran beat his Tea Party challenger, and was reelected to represent Mississippi in the Senate. Mia Love became the first black Mormon elected to the House of Representatives on the Republican ticket. She will join two other black Republicans in Washington: Tim Scott, the first black Senator to represent South Carolina since Reconstruction, and Will Hurd, the first black Republican from Texas to win a seat in the House of Representatives. I think it’s safe to say that the Republicans benefited from the current state of race in America more than the Democrats.

The contrasting images of black bodies in this past election tells us more about race in America than simply voter demographics and a series of new firsts. I wrote a book about bodies and race, Black Citizenship and Authenticity in the Civil Rights Movement. Instead of rehashing academic debates on how social movements start or end, I wanted to understand the civil rights movement’s impact on black political representation. I found two contrasting representations of black citizenship. The first was good black citizenship, the racially non-threatening form black political representation that reflects the idealized US citizen. Good black citizenship allowed for a narrow slice of black life to gain access to the political and economic world. The second was black authenticity, a racially threatening representation of black citizenship. Although the politics of black authenticity was originally intended to secure black political power at the local level, it became the basis for the criminalization of urban black life.

Now here’s the catch. The protester’s embodied performances to address the problems of police brutality and extreme poverty inadvertently reinforce the same racial stereotypes the protesters are trying to debunk. If the police attack the protesters, the protesters are blamed for the violence. If the protesters express any emotion or appear outraged at the police, the style of protest silences the message. The protests do not sway the general public to their side. The change in symbolic gesture is very telling about the current politics of black authenticity. In the late 1960s, it was the fist in the air. It meant securing black political power so that the black community had a say in shaping their future. Today, it’s hands in the air. There is even a hash tag, #handsup. Black authenticity’s signature protest is a gesture of surrender. It captures the dire sentiment of no hope or promise of a future in America’s marginalized black community.

Good black citizens do not address the plight of blacks on the margins. The national representation of good black citizenship cuts through party lines. For example, take the Democratic Senator from New Jersey, Cory Booker. Booker has been an enthusiastic supporter for charter schools, and has had no problem raising money from political donors. His response to the events in Ferguson skipped the issue of police brutality and extreme poverty, “I appreciate the challenges and complexities of the situation in Ferguson.” He called on Eric Holder to look into how the police handled the journalists covering the Ferguson protests. He called for an end to the violence. He remained calm during the interview. He did not address the continued criminalization of blacks on the margins.

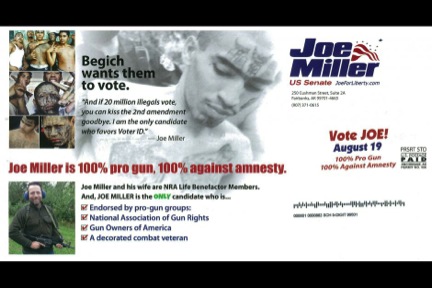

The Republican’s used representations of good black citizens and black authenticity bit differently than the Democrats. They used good black citizens to distance themselves from the overt racists in the Tea Party and mask pro-business neoliberal policy. Rand Paul reached out to the black community, specifically the NAACP. In an opt-ed for Time Magazine, he called for an end to the militarization of the police. He blamed the militarization of the police on big government. He did not blame teachers unions. He did not address the conduct of the police officers. Tea Party candidate Joe Miller challenged Dan Sullivan in the 2014 Republican primary in Alaska. Miller ran an overtly racist ad campaign, even for Tea Party standards.

The failure of the Democratic Party in 2014 is not because of billionaire funded Super PACS, Ebola, ISIS, or racism towards Barack Obama. Whites have continued to ignore the plight of blacks on the margins since the 1960s, while embracing good black citizens. Whether or not the police officer was within his legal rights to shoot Michael Brown is not the real issue in Ferguson. The real issue is that the political establishment can so willfully ignore the struggles of blacks on the margins of society, where police brutality is commonplace, and sometimes justified. However, the significance of black political representations is no longer confined to blacks like it was during the civil rights era. It is a national problem. Whites have to embrace the problems of the black community as if they were their problems. Whites cannot afford to identify with the neoliberal project. Poverty, crumbling infrastructure, ecological damage, and a dwindling safety net affect all of us. Our contemporary social problems cannot be solved by privatization, tax cuts, fiscal austerity, and more police officers. In the end, you have to wonder if the Democrats will adopt the Ferguson protesters’ embodied performance of raising their arms in the air for the 2106 elections.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed