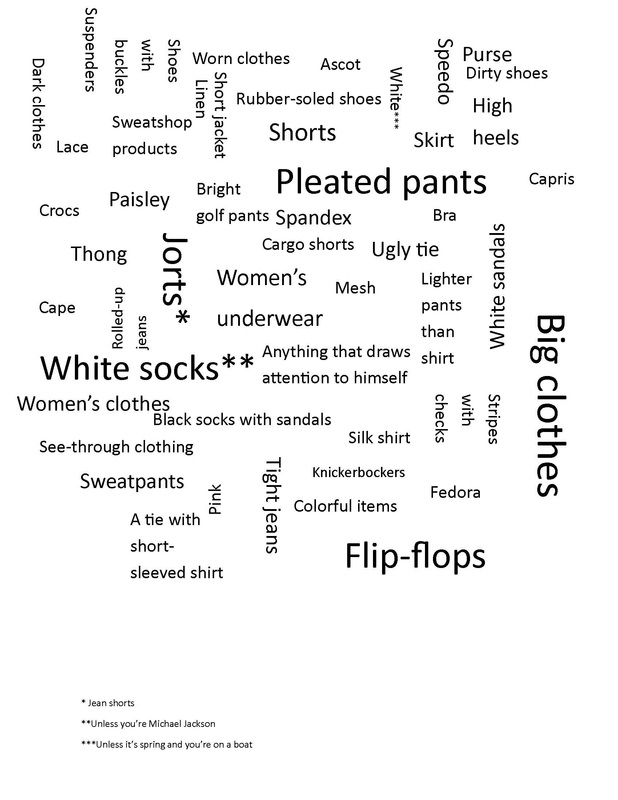

| Erynn Masi de Casanova, PhD, is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Cincinnati. She conducts research on the intersection of gender, work, and identity and is author of the award-winning book Making Up the Difference: Women, Beauty, and Direct Selling in Ecuador, among many other publications. Her new book on men’s work dress in corporate America, titled Buttoned Up: Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity, will be published by ILR/Cornell University Press this fall. by Erynn Masi de Casanova, Phd Associate Professor of Sociology University of Cincinnati As part of the research for my forthcoming book Buttoned Up: Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity (ILR/Cornell University Press), I asked 76 men to complete this sentence. Their answers are in this word cloud: |

1) White socks. Many interviewees thought that men should not wear white socks, especially to the office, in the words of one: “unless you’re Michael Jackson.” The prohibition relates to men’s desire to be seen as professional. White socks are seen as casual or athletic wear and thus unprofessional. Perhaps because white socks are associated with sports, they place men’s bodies on the body side of the mind/body split. Traditional masculinity values mind over body, an ideal that meshes well with white-collar work, seen as requiring brain rather than brawn.

2) Jorts. For those who don’t follow University of Kentucky basketball (I don’t) or come from the South (I do) or remember the early 90s (no comment), I should clarify that “jorts” is a mash-up of the words “jean” and “shorts.” Men mention jorts for at least two reasons: one, it’s a funny word and they enjoy saying it, and two, jorts are seen as incompatible with a middle- or upper-class appearance. Men’s bodies are seen as working-class or poor when they are wearing jorts. Jorts are uncool throwback gear, something that my interviewees maybe used to have in their closets but have long since donated to Goodwill.

3) Flip-flops. Some men think flip-flops are just fine, depending on the situation. Certainly these guys aren’t wearing dress shoes to the beach! But many see flip-flops as inappropriate in even the most casual workplace. This has to do with professionalism, but also with masculinity. Some men don’t like drawing attention to themselves and their dress, and the smacking sound that flip-flops make when you wear them does just that, according to one interviewee.

4) Pleated pants/Big clothes. So these are really two separate answers to the question of what a man should never wear, but they send the same message about masculinity and being current. The thinking—which showed up in many of my conversations with men about clothing—goes like this. Pleated pants make you look like you don’t know what’s in style. They also make you look bigger than you are, and not in a good way. Big, looser-fitting clothes are for men who don’t want people looking at their bodies, which fits with traditional ideas of masculinity. But changing norms of masculinity are making it increasingly acceptable to look at men’s bodies, and for men to want to be seen as bodies. So wearing flat-front pants or slimmer clothing is a way of staying current that signals new ways of thinking about masculinity.

5) Women’s clothes/Women’s underwear. (See also other answers: purse, high heels, capris, and more.) Given men’s frequent rejection of baggy clothing (see #4 above) and embracing of more body-conscious clothing, we might think that old ideas of masculinity have been totally thrown out the window. Not so fast. Popular answers to the question of what men should never wear included some version of “things that women wear.” So today’s white-collar masculinity sticks with the traditional definition of masculinity as anti-feminine. The bottom line: today’s white-collar men generally eschew clothing seen as feminine, while valuing professionalism, being open to the possibility that their bodies may be looked at by others, and staying in step with the times.

What would you contribute to the word cloud? What should a man never wear?

Learn more about the book: http:www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/?GCOI=80140100091120

RSS Feed

RSS Feed