Postdoctoral Research Associate

Department of Medical Education

University of Illinois at Chicago

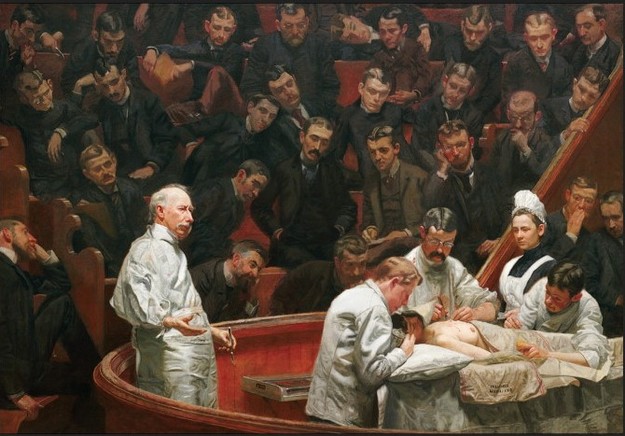

In classic studies of socialization in medical school, scholars wrote of the anatomy lab as a foundational experience for the formation of the physician-in-the-making’s self (see Becker, et al, 1961; Fox, 1988; Smith and Kleinman, 1988; Hafferty, 1991). By working with dead bodies during cadaver dissection, the medical student learned how to hide feelings of anxiety, disgust, and sadness. These formative experiences prepared future physicians for working with patients as passive objects under the medical gaze.

Critiques of (bio)medicine in the past three decades have advanced the idea that the patient’s body is socially constructed. Drawing on path-breaking works such as Michel Foucault’s Birth of the Clinic, scholars have demonstrated that the patient-body is produced as an object under the medical gaze through a range of techniques, practices, and discourses. As such, critics of biomedicine have unpacked how the patient-body is constructed in a myriad of contexts. In more applied contexts, scholars in the health humanities and health professions education have attempted to re-instill notions of the patient as more than just a body-object into medical trainees. However, while the construction of the patient-body has been thoroughly interrogated, few scholars have considered the construction of the physician-body in biomedicine.

I consider this very question through the lens of the medical habitus (Underman, 2015). The medical habitus “allows scholars to move beyond purely cognitive models of socialization to consider the transformation of thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and embodiment of medical students as they adapt to medical culture” (Underman, 2015: 181). Previously, scholars of socialization in medical education examined how the medical student learns to play “his” role in the clinic, as in Howard Becker et al’s classic study Boys in White. Other scholars, such as Frederic Hafferty, described the role of the hidden curriculum in medical student socialization, demonstrating how latent rules and norms transmit lessons about medical values. While these perspectives are important, I argue that using the medical habitus as a framework to understand the adoption of a professional (clinical) identity better captures the embodied and emotional (or affective) dimensions of this medical socialization.

My research examines how medical students learn the pelvic exam on a specially-trained layperson called a gynecological teaching associate (GTA) I selected GTA programs as a case study to understand how simulated patient experiences lead to the adoption of the medical habitus. I show in my work that GTA programs emerged in the 1970s and 1980s in response to critiques in the Women’s Health Movement about how medical students were taught the pelvic exam—usually on indigent clinic patients. Around the same time, medical educators were launching similar critiques of how the pelvic exam was taught. These educators argued that existing models were ineffective because students were often too nervous or unable to ask questions of either their faculty or the person they were examining. GTA programs addressed these critiques by using trained laypeople to teach the pelvic exam. In a typical session, a GTA will walk a group of two to three medical students through a complete, patient-friendly pelvic exam using the GTA’s own body as the model (Underman, 2011). These programs have become ubiquitous, with over 90% of medical schools in the United States and Canada using GTAs (Beckmann, et al, 1988).

The framework of the medical habitus is useful here because it allows me to focus on the range of embodied dispositions and attitudes that medical students adopt during the GTA session, especially with regard to emotion. Norms and values about centering the patient in the pelvic exam and involving the patient actively in their own healthcare become embodied in complicated and sometimes contradictory ways. This is especially important, as there has been a shift recently toward an increased emphasis on empathy in the clinical encounter (Underman and Hirshfield, 2016). In the GTA session in particular, empathy is as much an affective state as it is a performance of skills and behaviors necessary for eliciting the patient’s cooperation. For example, during the speculum exam, medical students are taught strategies like using non-threatening language (“bills” instead of “blades”) and giving the patient a warning touch on the inner thigh before making contact with the genitals. These strategies ostensibly are for the patient’s comfort and relaxation. However, they also make the physician’s job of performing the exam easier, since a relaxed patient is more compliant.

The crafting of the physician-body in medical education is a fascinating topic and ought to be considered by more scholars studying the body and embodiment. Scholars in science and technology studies (Prentice, 2012; Harris, 2016) have considered this more in-depth, and it remains an important topic for consideration. Through my work, I argue that we should consider how it is that patient-bodies and physician-bodies are constructed through an entanglement of discourses, practices, and techniques in medical education. We know that bodies don’t exist in isolation of the social practices and structures within which they move, and medical school is no exception. By exploring new technologies of simulation and drawing from new theoretical tools, I intend to more fully understand what happens to the medical gaze when the patient sits up and talks back.

Kelly Underman, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Department of Medical Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests include medical education, the body and embodiment, affect studies, and the politics of knowledge production. Her work has been published in Social Science & Medicine, Gender & Society, Social Studies of Science, and Sociology Compass.

Becker, Howard S., Blanche, Geer, Everett, C. Hughes, Anselm, L. Strauss, 1961. Boys

in White: Student Culture in Medical School. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

Beckmann, Charles R. B., B. M. Barzansky, B. F. Sharf, and K. Meyers. 1988. “Teaching Gynaecological Teaching Associates.” Medical Education, 22 (2): 124-31.

Fox, Renee C., 1988. Essays in Medical Sociology: Journeys into the Field. Transaction

Books: New Brunswick, NJ.

Hafferty, Frederic W., 1991. Into the Valley: Death and the Socialization of Medical

Students. Yale University Press: New Haven.

Harris, Anna. 2016. "Listening-touch, Affect and the Crafting of Medical Bodies through Percussion." Body & Society, 22(1): 31-61.

Prentice, Rachel. 2012. Bodies in Formation: An Ethnography of Anatomy and Surgery

Education. Duke University Press: Durham, NC.

Smith, Allen C., Kleinman, Sherryl, 1989. “Managing Emotions in Medical School:

Students’ Contacts with the Living and the Dead.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 52(1), 56-69.

Underman, Kelly. 2011. “’It's the Knowledge that Puts You in Control’: The Embodied

Labor of Gynecological Educators.” Gender & Society, 25(4), 431-450.

Underman, Kelly, 2015. “Playing Doctor: Simulation in Medical School as Affective

Practice.” Social Science & Medicine, 136-137: 180-188.

Underman, Kelly, and Laura E. Hirshfield. 2016. "Detached Concern?: Emotional Socialization in Twenty-First Century Medical Education." Social Science & Medicine, 160: 94-101.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed