University of California-San Francisco

In his 2000 review of the literature on space and place, Thomas Gieryn invites sociologists to emplace their work, arguing that a place-sensitive sociology operates in a visual key. He develops three necessary and sufficient conditions for the making of place: a place has a geographic location, it has materiality, and it is invested with meaning and value. The places he reviews are all of the brick-and-mortar type (villages, parks, etc.), and his definition of materiality implies “stuff”: “Place has physicality. Whether built or just come upon, artificial or natural ... place is stuff. It is a combination of things or objects at some particular spot in the universe” (Gieryn, 2000, p. 465).

My ethnographic work in intensive care units (ICUs) with Myles Leslie, Scott Reeves, and Simon Kitto has shown that place can be fleeting, temporary, and still be invested with meaning through a materiality that is made of… bodies. This insight came from the study of medical rounds, a ubiquitous practice in teaching hospitals. Rounds are a medical ritual whereby the whole medical team gets up to speed on its patients through case presentations; case discussions; care plan development and discussions; and, sometimes, patient visits. They occur in the morning and are supervised by the attending physician, who is the senior doctor in charge of training medical students, interns, residents, and fellows.

Rounds have been the object of previous sociological scrutiny (Arluke, 1980; Atkinson, 1995), but our work focuses on redefining the materiality of place. How can bodies be material enough to make a place? During rounds, the bodies of physicians create a visible and partly impermeable boundary that protects medical knowledge and expertise. This boundary makes it difficult for other personnel and patients to get in.

Here, I present some examples of the consequences this barrier creates to illustrate how bodies create the materiality of rounds:

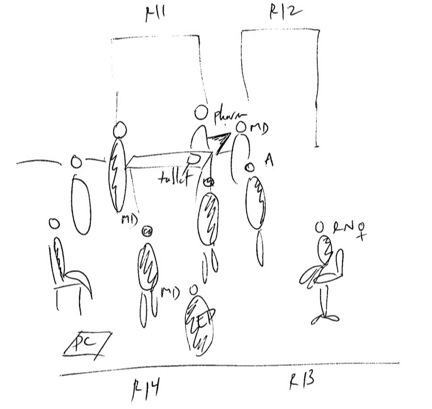

Example 1. Observations – Hilltop, December 20, 2012

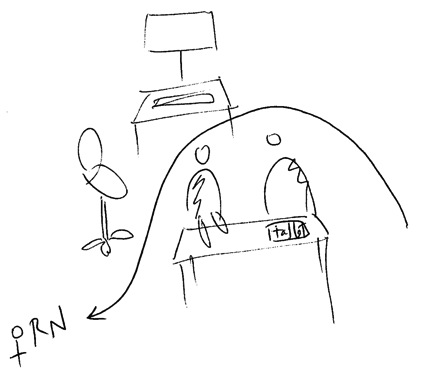

Patient 13 is being sent to CT and has to be rolled through the rounding team to leave the unit. I am in the way, help move some stuff around. ICU rounds are in the way and have to be told to move to make room for the bed. The team of 5 MDs and a pharmacist are standing in the middle of the hallway. I try to get through the group to do something else but have to stay behind them or interrupt. Dave, a tall white RN walks through. Another MD joins the rounding group, for a total of 6. Melissa, a short RN, is standing behind them, on the chair by Room 13, as the group discusses her patient.

Example 2. Interview with Nancy, September 6, 2013

Elise: So one of the things that I have noticed is when they [the doctors] do their rounds, they make a circle.

Nancy [RN]: Right, try and get around them, it’s close to impossible.

Elise: Yeah, so you find it a struggle to get around them physically? They take a lot of space. Anything else you notice about

their circle formation?

Nancy: Well, you have to fight to get in it. As a nurse, as a person at the bedside, I will walk through the whole thing. I'll say,

“Excuse me,” and I'll kind of go in there, and I want to hear. …

Elise: Yeah.

Nancy: But if you say, “Excuse me,” and they don't move out of the way a couple times, and I'm like, “Excuse me,” and then

I'll touch them. I generally don't touch people.

Elise: But in that case –

Nancy: You have to.

What we learn from this second example, and others like it, that to get attention from doctors, nurses and other ICU professionals often have to raise their voices or physically break the circle of bodies that create the place of rounds. Doctors unconsciously stand in front of other personnel, excluding them; many nurses, faced with potential failure or humiliation (e.g. eye rolling), develop workarounds: pre-rounding, negotiations.

To summarize, rounds are a mostly impermeable space, whose membrane is negotiated carefully. The embodied materiality of rounds—the barrage of physicians’ bodies and their props—protects what is considered to be a sacred moment and place for teaching, learning, and planning among doctors. Paying attention to the spatial grammar of rounds highlights the way interprofessional hierarchies are reproduced and challenged. It also shows that rounds, even though impermanent, fleeting and shifting, are a place: they are geographically located within the ICU. And although mobile, they have an embodied materiality as they hold meaning and value for both those who are included and those who are excluded.

References

Arluke, Arnold. (1980). Roundsmanship: inherent control on a medical teaching ward. Social Science & Medicine. Part A: Medical Psychology & Medical Sociology, 14(4), 297-302.

Atkinson, Paul. (1995). Medical talk and medical work: Sage.

Gieryn, Thomas F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 463-496.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed